Lists (they are my subjective groupings, of course) group the statues into categories and sets of analogous images,

and are intended as an aid to cross-referencing and comparison. The aim of this work is to offer some kind of a handle on such a prodigious

creation, and to put its otherworldly wealth of imagery (with correlating information) into the hands of interested persons.

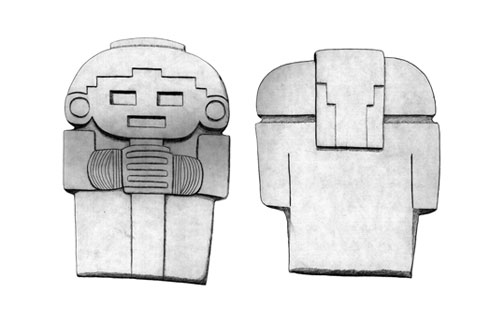

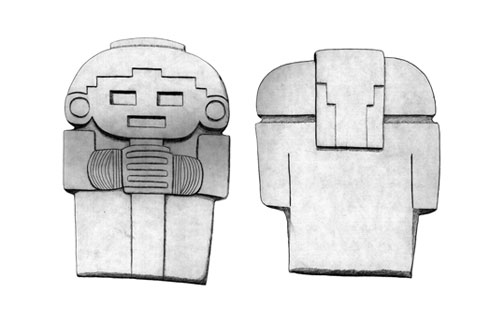

All of the statues illustrated in this catalogue are stonesculptures the author has personally seen, and drawn while viewing them. None of the illustrations seen here were made from photographs or any other form of reproduction, nor are items included which have been merely referred to or described.

All of the statues illustrated in this catalogue are stonesculptures the author has personally seen, and drawn while viewing them. None of the illustrations seen here were made from photographs or any other form of reproduction, nor are items included which have been merely referred to or described.

*********************

In the wake of the ravaging of american culture, not too much is known about the Pueblo Escultor stone-sculptors, but

this much is clear: the many hundreds of stone statues carved and then left buried underground by these long-forgotten artists—an imagery to

be seen in its magnificent profusion on the present website— constitute the largest and richest, the greatest lithic library ever

created in ancient America. Each statue, written in a language we no longer master, represents a ‘text’ from the shelves of this great

library, reciting tales of the beliefs and practices, the personages of the otherworld, the cosmic events in the mythology of the Pueblo

Escultor.

The usual name associated with these sculpted monoliths is San Agustín, rather than Pueblo Escultor. San Agustín is the label typically used in the archaeological literature, and it is the name of the area’s principal town; but Pueblo Escultor —the name coined in 1892 by the first colombian investigator— is a much better title form the ancient stone-sculptors.

The usual name associated with these sculpted monoliths is San Agustín, rather than Pueblo Escultor. San Agustín is the label typically used in the archaeological literature, and it is the name of the area’s principal town; but Pueblo Escultor —the name coined in 1892 by the first colombian investigator— is a much better title form the ancient stone-sculptors.

San Agustín is a small town or pueblo in the uplands of southern Colombia, in the departamento (or state)

of Huila, near the headwaters of the region’s main waterway, today called the Magdalena River. The mountains behind San Agustín pertain to

the collision of Colombia’s three cordilleras (or ranges) into one great massif known as the Macizo Colombiano, a voluminous mountainous knot

which unites the country’s three southern departamentos (Huila, Cauca, and Nariño).

The pueblo lies above the Magdalena in the broadest valley of the Macizo, at an altitude of some 1700 meters. It is a land of continual, smiling beauty and majesty, a magical land, pulsing with life-force, coursing with water and clothed in tropical vegetation, a green, vibrant world; a land watched over by a special, enchanted star, enfolded in a transcendental, time-spanning aura. And the waterfalls and canyons, the everliving forests, the hummingbirds and orchids and the entire riot of fauna and flora come from all the neighboring regions, the endlessly mellow climate and the eternal tropical time-continuum, the snow-caps on the horizon, the vast abundance of the bounty of the pachamama—surely all this framed and impregnated the world of the statue-makers long ago, filled and oriented them each day (as it does us), and nurtured them into the creators they became, another, magnificent link in a now-nebulous chain.

About 75% of the Pueblo Escultor statuary here presented is from San Agustín’s valley, either from its Archaeological Park area or from other outlying valley sites. The remaining quarter are from other, smaller statue-nuclei, other Pueblos Escultores, elsewhere among the mountainfolds of the Macizo, in statue-areas such as Moscopán, Aguabonita and Platavieja in the La Plata River drainage, and Tierradentro in the valley of the Paéz River. Some stone-carvings may date from as early as several centuries b.c.e. (before current era), while others may be from as late as 7 or 8 centuries c.e. In any case, it’s probable that this land was a fertile center of sculpture over a very long period measured in many centuries; a carved wooden sarcophagus dates from 555 b.c.e. There are also ancient statue zones of uncertain date in Cauca to the west and in Nariño to the south. Pueblo Escultor statues were created in sites scattered throughout the Macizo.

The pueblo lies above the Magdalena in the broadest valley of the Macizo, at an altitude of some 1700 meters. It is a land of continual, smiling beauty and majesty, a magical land, pulsing with life-force, coursing with water and clothed in tropical vegetation, a green, vibrant world; a land watched over by a special, enchanted star, enfolded in a transcendental, time-spanning aura. And the waterfalls and canyons, the everliving forests, the hummingbirds and orchids and the entire riot of fauna and flora come from all the neighboring regions, the endlessly mellow climate and the eternal tropical time-continuum, the snow-caps on the horizon, the vast abundance of the bounty of the pachamama—surely all this framed and impregnated the world of the statue-makers long ago, filled and oriented them each day (as it does us), and nurtured them into the creators they became, another, magnificent link in a now-nebulous chain.

About 75% of the Pueblo Escultor statuary here presented is from San Agustín’s valley, either from its Archaeological Park area or from other outlying valley sites. The remaining quarter are from other, smaller statue-nuclei, other Pueblos Escultores, elsewhere among the mountainfolds of the Macizo, in statue-areas such as Moscopán, Aguabonita and Platavieja in the La Plata River drainage, and Tierradentro in the valley of the Paéz River. Some stone-carvings may date from as early as several centuries b.c.e. (before current era), while others may be from as late as 7 or 8 centuries c.e. In any case, it’s probable that this land was a fertile center of sculpture over a very long period measured in many centuries; a carved wooden sarcophagus dates from 555 b.c.e. There are also ancient statue zones of uncertain date in Cauca to the west and in Nariño to the south. Pueblo Escultor statues were created in sites scattered throughout the Macizo.

Eventually, some seven centuries before the coming of the european invaders, the Pueblo Escultor, as sculptors and

cosmogenitors, had come to the end of their long run and vanished from the scene. As people, though, they may well have continued to

live in their homeland Macizo, albeit no longer sculptors and creators of a “library”: current evidence demonstrates that the

statue-areas of San Agustín and the other statue-nuclei continued to be inhabited, and probably grew in population, though no more

sculptures appeared, during those final post-Pueblo Escultor centuries.

It was not during those last seven centuries of Macizo life prior to the invasion, but rather at the beginning of the succeeding centuries of spanish “rule”, that the once-civilized lands of the Macizo were (brutally) emptied of most of their human population, with much of the land reverting to naturaleza. This, and the fact that the Pueblo Escultor left little in the way of lasting vestiges aboveground, helps to explain why the discovery of these ancient ruins in the Macizo seemed so improbable, and took so long to come about. The masterful work created to endure the ages had all been left underground, hidden away from the “superficial” world, laid in the womb of the pachamama.

It was not during those last seven centuries of Macizo life prior to the invasion, but rather at the beginning of the succeeding centuries of spanish “rule”, that the once-civilized lands of the Macizo were (brutally) emptied of most of their human population, with much of the land reverting to naturaleza. This, and the fact that the Pueblo Escultor left little in the way of lasting vestiges aboveground, helps to explain why the discovery of these ancient ruins in the Macizo seemed so improbable, and took so long to come about. The masterful work created to endure the ages had all been left underground, hidden away from the “superficial” world, laid in the womb of the pachamama.

So the discoveries of the many statues have been principally a

process of the last century and a half. And they have had little

impact, have been mostly ignored or forgotten, have remained

difficult of access, little taken into account by those who interpret

and write the histories, who analyze and bring the disparate

elements into the general discourse and paint for us the picture of

the mysteries of our past. Toss in the carelessness and negligence

of those whose office has been to guard and protect these statues,

administered from Bogotá, with San Agustín a hard-to-reach

backwater at the far southern end of the country.

We can grasp a new level of significance to the vast statueburials in the Macizo, in the Magdalena headwaters, by understanding that the statuary comprises not just a magnificent artistic display, and not just a great repository of ancient knowledge. In addition, and preeminent, is the fact that the corpus, the entirety, makes up a vast pagamento, a “payment/offering,” in the tradition that has always existed in the Andes, and that exists now in Colombia, among our indigenous neighbors. Burials—funerary phenomena from the point of view of modernity—would be above all, in the ancient-and-contemporary american spiritual world, pagamentos, that is, compact-offerings made to assure the bounty and harmony of nature, of the pachamama, in exchange for our reverence for and custodianship of the natural world and all its lives and systems.

And above all, our stewardship of the water, and our care for the rivers. That this greatest of all pagamentos, the burial of the statuary with all that accompanied it, was laid in the ground at the headwaters of the rivers, and of the Great River itself, cannot be born of coincidence. All of this points toward the ultimate sense and mystery of the statuary of the Pueblo Escultor, the essential message sent by the ancestral sculptors to all future custodians, ourselves included. The statues were set dreaming in the earth to guard and care for the sources of the rivers, and the world that surrounds those magical generative places. We ignore that at our peril.

We can grasp a new level of significance to the vast statueburials in the Macizo, in the Magdalena headwaters, by understanding that the statuary comprises not just a magnificent artistic display, and not just a great repository of ancient knowledge. In addition, and preeminent, is the fact that the corpus, the entirety, makes up a vast pagamento, a “payment/offering,” in the tradition that has always existed in the Andes, and that exists now in Colombia, among our indigenous neighbors. Burials—funerary phenomena from the point of view of modernity—would be above all, in the ancient-and-contemporary american spiritual world, pagamentos, that is, compact-offerings made to assure the bounty and harmony of nature, of the pachamama, in exchange for our reverence for and custodianship of the natural world and all its lives and systems.

And above all, our stewardship of the water, and our care for the rivers. That this greatest of all pagamentos, the burial of the statuary with all that accompanied it, was laid in the ground at the headwaters of the rivers, and of the Great River itself, cannot be born of coincidence. All of this points toward the ultimate sense and mystery of the statuary of the Pueblo Escultor, the essential message sent by the ancestral sculptors to all future custodians, ourselves included. The statues were set dreaming in the earth to guard and care for the sources of the rivers, and the world that surrounds those magical generative places. We ignore that at our peril.

The ancient language of the statues appears to be lost. But the stones, after their many centuries beneath

the earth’s surface, still speak to us, still communicate...

see the statues

The Pueblo Escultor were the sculptors of the greatest “stone library” ever created in ancient America, in the

valley of San Agustín and the Macizo Colombiano of southern Colombia.